The theory of attachment was originally developed by John Bowlby (1907 - 1990), a British psychoanalyst who was attempting to understand the intense distress experienced by infants who had been separated from their parents. Bowlby observed that separated infants would go to extraordinary lengths (e.g., crying, clinging, frantically searching) to either prevent separation from their parents or to reestablish proximity to a missing parent. At the time, psychoanalytic writers held that these expressions were manifestations of immature defense mechanisms that were operating to repress emotional pain, but Bowlby noted that such expressions are common to a wide variety of mammalian species, and speculated that these behaviors may serve an evolutionary function.

Drawing on ethological theory, Bowlby postulated that these attachment behaviors, such as crying and searching, were adaptive responses to separation from with a primary attachment figure--someone who provides support, protection, and care. Because human infants, like other mammalian infants, cannot feed or protect themselves, they are dependent upon the care and protection of "older and wiser" adults. Bowlby argued that, over the course of evolutionary history, infants who were able to maintain proximity to an attachment figure (i.e., by looking cute or by expressing in attachment behaviors) would be more likely to survive to a reproductive age. According to Bowlby attachment, a motivational-control system, what he called the attachment behavioral system, was gradually "designed" by natural selection to regulate proximity to an attachment figure.

Background: Bowlby Attachment theories

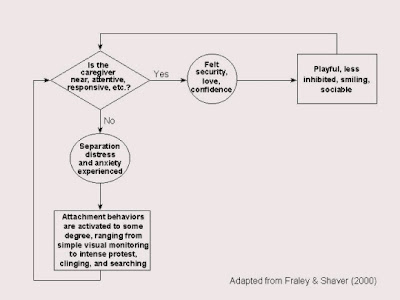

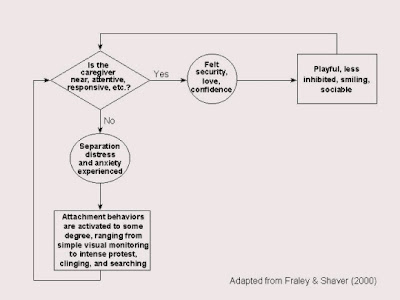

The attachment behavior system is an important concept in attachment theory because it provides the conceptual linkage between ethological models of human development and modern theories on emotion regulation and personality. According to Bowlby, the attachment system essentially "asks" the following fundamental question: Is the attachment figure nearby, accessible, and attentive? If the child perceives the answer to this question to be "yes," he or she feels loved, secure, and confident, and, behaviorally, is likely to explore his or her environment, play with others, and be sociable. If, however, the child perceives the answer to this question to be "no," the child experiences anxiety and, behaviorally, is likely to exhibit attachment behaviors ranging from simple visual searching on the low extreme to active following and vocal signaling on the other (see Figure 1). These behaviors continue until either the child is able to reestablish a desirable level of physical or psychological proximity to the attachment figure, or until the child "wears down," as may happen in the context of a prolonged separation or loss. In such cases or helplessness, Bowlby believed the child experiences despair and depression.

Individual Differences in Infant Attachment Patterns

Although Bowlby believed that the basic dynamics described above captured the normative dynamics of the attachment behavioral system, he recognized that there are individual differences in the way children appraise the accessibility of the attachment figure and how they regulate their attachment behavior in response to a threat. However, it wasn't until his colleague, Mary Ainsworth, began to systematically study infant-parent separations that a formal understanding of these individual differences was articulated. Ainsworth and her students developed a technique called the strange situation--a laboratory paradigm for studying infant-parent attachment. In the strange situation, 12-month-old infants and their parents are brought to the laboratory and, systematically, separated and reunited. In the strange situation, most children (i.e., about 60%) behave in the way implied by Bowlby's "normative" theory. They become upset when the parent leaves the room, but, when he or she returns, they actively seek the parent and are easily comforted by him or her. Children who exhibit this pattern of behavior are often called secure. Other children (about 20% or less) are ill-at-ease initially, and, upon separation, become extremely distressed. Importantly, when reunited with their parents, these children have a difficult time being soothed, and often exhibit conflicting behaviors that suggest they want to be comforted, but that they also want to "punish" the parent for leaving. These children are often called anxious-resistant. The third pattern of attachment that Ainsworth and her colleagues documented is called avoidant. Avoidant children (about 20%) don't appear too distressed by the separation, and, upon reunion, actively avoid seeking contact with their parent, sometimes turning their attention to play objects on

the laboratory floor. Ainsworth's work was important for at least three reasons. First, she provided one of the first empirical demonstrations of how attachment behavior is patterned in both safe and frightening contexts. Second, she provided the first empirical taxonomy of individual differences in infant attachment patterns. According to her research, at least three types of children exist: those who are secure in their relationship with their parents, those who are anxious-resistant, and those who are anxious-avoidant. Finally, she demonstrated that these individual differences were correlated with infant-parent interactions in the home during the first year of life. Children who appear secure in the strange situation, for example, tend to have parents who are responsive to their needs. Children who appear insecure in the strange situation (i.e., anxious-resistant or avoidant) often have parents who are insensitive to their needs, or inconsistent or rejecting in the care they provide.

Adult Romantic Relationships

Although Bowlby was primarily focused on understanding the nature of the infant-caregiver relationship, he believed that attachment characterized human experience from "the cradle to the grave." It was not until the mid-1980's, however, that researchers began to take seriously the possibility that attachment processes may play out in adulthood. Hazan and Shaver (1987) were two of the first researchers to explore Bowlby's ideas in the context of romantic relationships. According to Hazan and Shaver, the emotional bond that develops between adult romantic partners is partly a function of the same motivational system--the attachment behavioral system--that gives rise to the emotional bond between infants and their caregivers. Hazan and Shaver noted that infants and caregivers and adult romantic partners share the following features:

- both feel safe when the other is nearby and responsive

- both engage in close, intimate, bodily contact

- both feel insecure when the other is inaccessible

- both share discoveries with one another

- both play with one another's facial features and exhibit a mutual fascination and preoccupation with one another

- both engage in "baby talk"

On the basis of these parallels, Hazan and Shaver argued that adult romantic relationships, like infant-caregiver relationships, are attachments, and that romantic love is a property of the attachment behavioral system, as well as the motivational systems that give rise to caregiving and sexuality.

Three Implications of Adult Attachment Theory

The idea that romantic relationships may be attachment relationships has had a profound influence on modern research on close relationships. There are at least three critical implications of this idea. First, if adult romantic relationships are attachment relationships, then we should observe the same kinds of individual differences in adult relationships that Ainsworth observed in infant-caregiver relationships. We may expect some adults, for example, to be secure in their relationships--to feel confident that their partners will be there for them when needed, and open to depending on others and having others depend on them. We should expect other adults, in contrast, to be insecure in their relationships. For example, some insecure adults may be anxious-resistant: they worry that others may not love them completely, and be easily frustrated or angered when their attachment needs go unmet. Others may be avoidant: they may appear not to care too much about close relationships, and may prefer not to be too dependent upon other people or to have others be too dependent upon them.

Second, if adult romantic relationships are attachment relationships, then the way adult relationships "work" should be similar to the way infant-caregiver relationships work. In other words, the same kinds of factors that facilitate exploration in children (i.e., having a responsive caregiver) should facilitate exploration among adults (i.e., having a responsive partner). The kinds of things that make an attachment figure "desirable" for infants (i.e., responsiveness, availability) are the kinds of factors we should find desirable in adult romantic partners. Importantly, individual differences in attachment should influence relational and personal functioning in adulthood in the same way they do in childhood.

Third, whether an adult is secure or insecure in his or her adult relationships may be a partial reflection of his or her attachment experiences in early childhood. Bowlby believed that the mental representations or working models (i.e., expectations, beliefs, "rules" or "scripts" for behaving and thinking) that a child holds regarding relationships are a function of his or her caregiving experiences. For example, a secure child tends to believe that others will be there for him or her because previous experiences have led him or her to this conclusion. Once a child has developed such expectations, he or she will tend to seek out relational experiences that are consistent with those expectations and perceive others in a way that is colored by those beliefs. According to Bowlby, this kind of process should promote continuity in attachment patterns over the life course, although it is possible that a person's attachment pattern will change if his or her relational experiences are inconsistent with his or her expectations. In short, if we assume that adult relationships are attachment relationships, it is possible that children who are secure as children will grow up to be secure in their romantic relationships.

In the sections below I briefly address these three implications in light of early and contemporary research on adult attachment.

Do We Observe the Same Kinds of Attachment Patterns Among Adults that We Observe Among Children?

The earliest research on adult attachment involved studying the association between individual differences in adult attachment and the way people think about their relationships and their memories for what their relationships with their parents are like. Hazan and Shaver (1987) developed a simple questionnaire to measure these individual differences. (These individual differences are often referred to as attachment styles, attachment patterns, attachment orientations, or differences in the organization of the attachment system.) In short, Hazan and Shaver asked research subjects to read the three paragraphs listed below, and indicate which paragraph best characterized the way they think, feel, and behave in close relationships:

A. I am somewhat uncomfortable being close to others; I find it difficult to trust them completely, difficult to allow myself to depend on them. I am nervous when anyone gets too close, and often, others want me to be more intimate than I feel comfortable being.

B. I find it relatively easy to get close to others and

am comfortable depending on them and having them depend on me. I don't worry about being abandoned or about someone getting too close to me.

C. I find that others are reluctant to get as close as I would like. I often worry that my partner doesn't really love me or won't want to stay with me. I want to get very close to my partner, and this sometimes scares people away.

Based on this three category measure, Hazan and Shaver found that the distribution of categories was similar to that observed in infancy. In other words, about 60% of adults classified themselves as secure (paragraph B), about 20% described

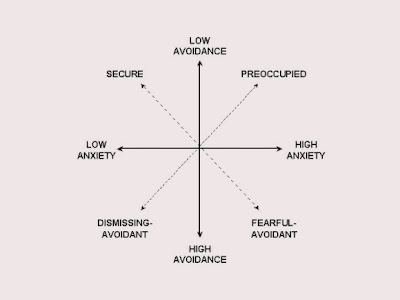

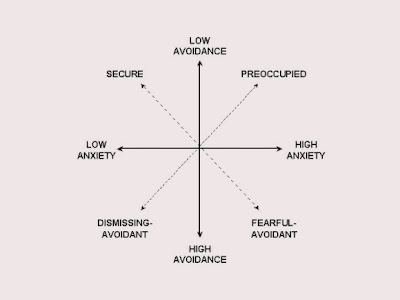

themselves as avoidant (paragraph A), and about 20% described themselves as anxious-resistant (paragraph C). Although this measure served as a useful way to study the association between attachment styles and relationship functioning, it didn't allow a full test of the hypothesis that the same kinds of individual differences observed in infants might be manifest among adults. (In many ways, the Hazan and Shaver measure assumed this to be true.) Subsequent research has explored this hypothesis in a variety of ways. For example, Kelly Brennan and her colleagues collected a number of statements (e.g., "I believe that others will be there for me when I need them") and studied the way these statements "hang together" statistically (Brennan, Clark, & Shaver, 1998). Brennan's findings suggested that there are two fundamental dimensions with respect to adult attachment patterns (see Figure 2). One critical variable has been labeled attachment-related anxiety. People who score high on this variable tend to worry whether their partner is available, responsive, attentive, etc. People who score on the low end of this variable are more secure in the perceived responsiveness of their partners. The other critical variable is called attachment-related avoidance. People on the high end of this dimension prefer not to rely on others or open up to others.

People on the high end of this dimension prefer not to rely on others or open up to others. People on the low end of this dimension are more comfortable being intimate with others and are more secure depending upon and having others depend upon them. A prototypical secure adult is low on both of these dimensions.

Brennan's findings are critical because recent analyses of the statistical patterning of behavior among infants in the strange situation reveal two functionally similar dimensions: one that captures variability in the anxiety and resistance of the child and another that captures variability in the child's willingness to use the parent as a safe haven for support (see Fraley & Spieker, 2003a, 2003b). Functionally, these dimensions are similar to the two-dimensions uncovered among adults, suggesting that similar patterns of attachment exist at different points in the life span.

In light of Brennan's findings, as well as taxometric research published by Fraley and Waller (1998), most researchers currently conceptualize and measure individual differences in attachment dimensionally rather than categorically. The most popular measures of adult attachment style are Brennan, Clark, and Shaver's (1998) ECR and Fraley, Waller, and Brennan's (2000) ECR-R--a revised version of the ECR. [Click here to take an on-line quiz designed to determine your attachment style based on these two dimensions.] Both of these self-report instruments provide continuous scores on the two dimensions of attachment-related anxiety and avoidance.

Do Adult Romantic Relationships "Work" in the Same Way that Infant-Caregiver Relationships Work?

There is now an increasing amount of research that suggests that adult romantic relationships function in the same ways as infant-caregiver relationships, with some noteworthy exceptions, of course. Naturalistic research on adults separating from their partners at an airport demonstrated that behaviors indicative of attachment-related protest and caregiving were evident, and that the regulation of these behaviors was associated with attachment style (Fraley & Shaver, 1998). For example, while separating couples generally showed more attachment behavior than nonseparating couples, highly avoidant adults showed much less attachment behavior than less avoidant adults. In the sections below I discuss some of the parallels that have been discovered between the way that infant-caregiver relationships and adult romantic relationships function.

Partner selection

Cross-cultural studies suggest that the secure pattern of attachment in infancy is universally considered the most desirable pattern by mothers (see van IJzendoorn & Sagi, 1999). For obvious reasons there is no similar study asking infants if they would prefer a security-inducing attachment figure. Adults seeking long-term relationships identify responsive caregiving qualities, such as attentiveness, warmth, and sensitivity, as most "attractive" in potential dating partners (Zeifman & Hazan, 1997). Despite the attractiveness of secure qualities, however, not all adults are paired with secure partners. Some evidence suggests that people end up in relationships with partners who confirm their existing beliefs about attachment relationships (Frazier et al., 1997).

Secure base and safe haven behavior

In infancy, secure infants tend to be the most well adjusted, in the sense that they are relatively resilient, they get along with their peers and are well liked. Similar kinds of patterns have emerged in research on adult attachment. Overall, secure adults tend to be more satisfied in their relationships than insecure adults. Their relationships are characterized by greater longevity, trust, commitment, and interdependence (e.g., Feeney, Noller, & Callan, 1994), and they are more likely to use romantic partners as a secure base from which to explore the world (e.g., Fraley & Davis, 1997). A large proportion of research on adult attachment has been devoted to uncovering the behavioral and psychological mechanisms that promote security and secure base behavior in adults. There have been two major discoveries thus far. First and in accordance with attachment theory, secure adults are more likely than insecure adults to seek support from their partners when distressed. Furthermore, they are more likely to provide support to their distressed partners (e.g., Simpson et al., 1992). Second, the attributions that insecure individuals make concerning their partner's behavior during and following relational conflicts exacerbate, rather than alleviate, their insecurities (e.g., Simpson et al., 1996).

Avoidant Attachment and Defense Mechanisms

According to attachment theory, children differ in the kinds of strategies they adopt to regulate attachment-related anxiety. Following a separation and reunion, for example, some insecure children approach their parents, but with ambivalence and resistance, whereas others withdraw from their parents, apparently minimizing attachment-related feelings and behavior. One of the big questions in the study of infant attachment is whether children who withdraw from their parents--avoidant children--are truly less distressed or whether their defensive behavior is a cover-up for their true feelings of vulnerability. Research that has measured the attentional capacity of children, heart rate, or stress hormone levels suggests that avoidant children are distressed by the separation despite the fact that they come across in a cool, defensive manner.

Recent research on adult attachment has revealed some interesting complexities concerning the relationships between avoidance and defense. Although some avoidant adults, often called fearfully-avoidant adults, are poorly adjusted despite their defensive nature, others, often called dismissing-avoidant adults, are able to use defensive strategies in an adaptive way. For example, in an experimental task in which adults were instructed to discuss losing their partner, Fraley and Shaver (1997) found that dismissing individuals (i.e., individuals who are high on the dimension of attachment-related avoidance but low on the dimension of attachment-related anxiety) were just as physiologically distressed (as assessed by skin conductance measures) as other individuals. When instructed to suppress their thoughts and feelings, however, dismissing individuals were able to do so effectively. That is, they could deactivate their physiological arousal to some degree and minimize the attention they paid to attachment-related thoughts. Fearfully-avoidant individuals were not as successful in suppressing their emotions.

Are Attachment Patterns Stable from Infancy to Adulthood?

Perhaps the most provocative and controversial implication of adult attachment theory is that a person's attachment style as an adult is shaped by his or her interactions with parental attachment figures. Although the idea that early attachment experiences might have an influence on attachment style in romantic relationships is relatively uncontroversial, hypotheses about the source and degree of overlap between the two kinds of attachment orientations have been controversial.

There are at least two issues involved in considering the question of stability: (a) How much similarity is there between the security people experience with different people in their lives (e.g., mothers, fathers, romantic partners)? and (b) With respect to any one of these relationships, how stable is security over time?

With respect to this first issue, it appears that there is a modest degree of overlap between how secure people feel with their mothers, for example, and how secure they feel with their romantic partners. Fraley, for example, collected self-report measures of one's current attachment style with a significant parental figure and a current romantic partner and found correlations ranging between approximately .20 to .50 (i.e., small to moderate) between the two kinds of attachment relationships. [Click here to take an on-line quiz designed to assess the similarity between your attachment styles with different people in your life.]

With respect to the second issue, the stability of one's attachment to one's parents appears to be equal to a correlation of about .25 to .39 (Fraley, 2002). There is only one longitudinal study of which we are aware that assessed the link between security at age 1 in the strange situation and security of the same people 20 years later in their adult romantic relationships. This unpublished study uncovered a correlation of .17 between these two variables (Steele, Waters, Crowell, & Treboux, 1998).

The association between early attachment experiences and adult attachment styles has also been examined in retrospective studies. Hazan and Shaver (1987) found that adults who were secure in their romantic relationships were more likely to recall their childhood relationships with parents as being affectionate, caring, and accepting (see also Feeney & Noller, 1990).

Based on these kinds of studies, it seems likely that attachment styles in the child-parent domain and attachment styles in the romantic relationship domain are only moderately related at best. What are the implications of such findings for adult attachment theory? According to some writers, the most important proposition of the theory is that the attachment system, a system originally adapted for the ecology of infancy, continues to influence behavior, thought, and feeling in adulthood (see Fraley & Shaver, 2000). This proposition may hold regardless of whether individual differences in the way the system is organized remain stable over a decade or more, and stable across different kinds of intimate relationships.

Although the social and cognitive mechanisms invoked by attachment theorists imply that stability in attachment style may be the rule rather than the exception, these basic mechanisms can predict either long-run continuity or discontinuity, depending on the precise ways in which they are conceptualized (Fraley, 2002). Fraley (2002) discussed two models of continuity derived from attachment theory that make different predictions about long-term continuity even though they were derived from the same basic theoretical principles. Each model assumes that individual differences in attachment representations are shaped by variation in experiences with caregivers in early childhood, and that, in turn, these early representations shape the quality of the individual's subsequent attachment experiences. However, one model assumes that existing representations are updated and revised in light of new experiences such that older representations are eventually "overwritten." Mathematical analyses revealed that this model predicts that the long-term stability of individual differences will approach zero. The second model is similar to the first, but makes the additional assumption that representational models developed in the first year of life are preserved (i.e., they are not overwritten) and continue to influence relational behavior throughout the life course. Analyses of this model revealed that long-term stability can approach a non-zero limiting value. The important point here is that the principles of attachment theory can be used to derive developmental models that make strikingly different predictions about the long-term stability of individual differences. In light of this finding, the existence of long-term stability of individual differences should be considered an empirical question rather than an assumption of the theory.

In understanding how relationships are formed and maintained, one important issue concerns the frictions that can develop in a relationship, including the frictions that emerge as part of day-to-day living: "Why don't you ever do the dishes — why is it always me?" "Why is it that I'm usually the one who takes out the garbage; why can't you do your fair share?" Or: "Why is it that I'm always the one who reaches out to end our disagreements? Don't you know the words, ‘I'm sorry'?"

In understanding how relationships are formed and maintained, one important issue concerns the frictions that can develop in a relationship, including the frictions that emerge as part of day-to-day living: "Why don't you ever do the dishes — why is it always me?" "Why is it that I'm usually the one who takes out the garbage; why can't you do your fair share?" Or: "Why is it that I'm always the one who reaches out to end our disagreements? Don't you know the words, ‘I'm sorry'?"